Research

Welcome to the Spiderday Night Lab! We are visual ecologists, which means we study the complex evolutionary relationship between animals’ eyes, their environment, and how they use color, shape, and movement to talk with each other.

Current Research

How do 8 eyes evolve when tarantulas take to the trees?

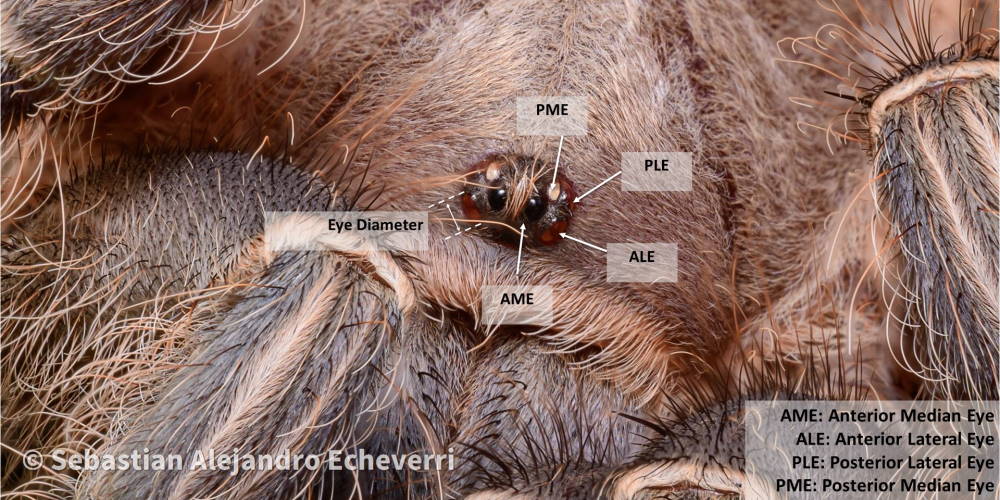

Figure 1. Tarantulas have 4 pairs of eyes, some of which may see differently and do different visual tasks.

Animals' environment and lifestyle can affect how their eyes evolve. Species that rely a lot on vision often evolve larger eyes, and vice versa. But most of what we know about eye size evolution is based on just a few “highly visual” groups of animals—mostly vertebrates and insects. But what about animals where vision seems unimportant? Do their eyes evolve the same way?

Tarantulas have small eyes compared to many other spiders, and scientists have assumed tarantulas don't use their vision for much. But, tarantulas live in many different environments—including ones that we know have led to changes in eye size in other animals—and male and female tarantulas have very different lifestyles as adults. We are comparing eye size with habitat and sex, across the evolutionary history of tarantulas. So far, we've found that arboreal species have larger eyes (relative to their body size) than terrestrial species in three of the four eye pairs, as do males of both habitats. It seems like, despite previous assumptions, arboreal tarantulas have experienced selection for improved (albeit still weak) vision!

High school student Lily Turri presented on our work-in-progress at the AAS 2021 conference; you can watch her talk on YouTube!

PhD Research

For a full presentation of my research, check out my PhD defense on YouTube! You can also find the PDF of my dissertation here.

How do the physics of light, sound, and smell determine how animals position themselves during communication?

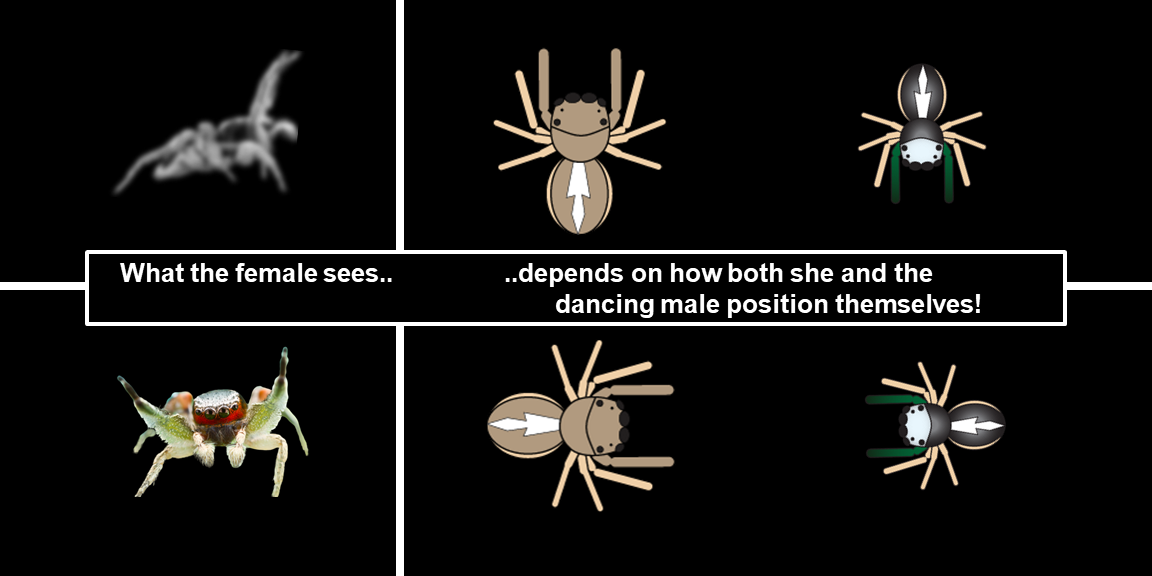

The way that animals--including us--communicate with each other is affected by where we are: our relative distance, direction, and location in the environment. Eyes, ears, noses, and other sensory organs have built-in spatial ("spacing-based") limitations. For example, you can't see behind yourself, its easier to smell something the nearer it gets, and it's harder to listen to a conversation in a loud room. Likewise, the ways we've evolved use colors + shapes, sound, and smells to communicate also face spatial challenges. Try reading a letter that is very far away from you, is turned to face away from you, or is in a dark room. When positioning isn't quite right for either end of the conversation (the sensory organ or the signal), you might miss out on part of the message (Fig 2).

Figure 2. For paradise jumping spiders (genus Habronattus) whether or not a dancing males' lovely colors can be seen by his female audience depends on how both animals position themselves. Males' colors can only be seen from the front, and only the spiders' forward-facing primary eyes can see in color. Photos and spider illustrations by Dr. Daniel Zurek.

Because it can be much easier to communicate if both the presenter and their audience move into the right positions, animals might be under pressure to evolve ways to make sure this happens. But, for a long time, we haven't studied this important part of communication. In the first part of my PhD, I reviewed the reasons behind the spatial limitations on sensors and signals, what (little) we know about how different animals position themselves, and how we can use new technology to learn more.

I published a revamped version of this review in Integrative and Comparative Biology (Echeverri et al. 2021), with the help of many valiant co-authors.

When paradise spiders dance, where does their audience look?

Male fiery-haired paradise spiders (Habronattus pyrrithrix) put on a spectacular song and dance show to impress females, but there's a potential problem. Males' colors can only be seen from the front, and while the spiders' eight eyes give them an almost 360-degree field of view, some of those eyes see differently. Only the spiders' forward-facing primary eyes can see in color and in high-resolution. Their multiple pairs of secondary eyes are great for detecting movement, but see in black-and-white and blurrier. So, what she sees depends on how both spiders move (Fig 2)!

Figure 2. Female H. pyrrithrix don't always pay full attention to courting males. Still from a video by Dr. Daniel Zurek and I.

How big of a problem is this? By tracking the behavior of males and females during courtship, I discovered that, on average, females can see a male’s colors only 30% of the time! While males always aimed their dancing towards females, females often turned to face elsewhere (perhaps watching for predators, or prey). In the second part of their courtship, males seem to wait until females are watching before showing off their more impressive dance moves.

I published this research in Behavioral Ecology (Echeverri et al. 2017), and it was covered by Popular Science.

How best to catch her (primary) eyes?

To increase the chances that his colors are visible, H. pyrrithrix males may have evolved ways to get females to turn and face him. In the first part of their dance, males repeatedly wave their 1st pair of legs up and down, just like we might flag down someone from a distance. But, what's going on around the male might change how easily he stands out.

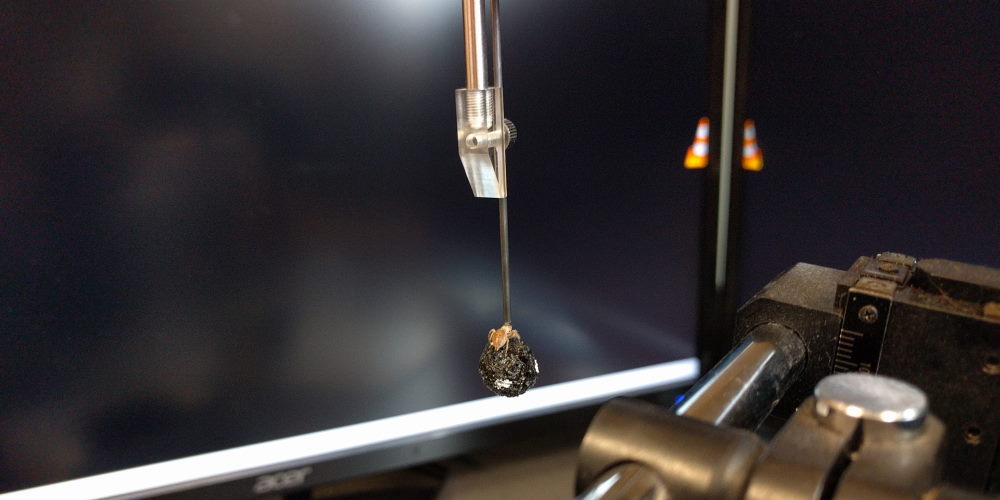

Figure 4. To find out what females found more interesting, we showed her videos on two computer monitors. We could tell what she wanted to look at based on the direction that she spun the foam ball she was holding.

By asking female spiders to choose between looking at animations of waving and non-waving males presented on different backgrounds, I learned that these movements are an excellent way of getting her attention. And, by filming real males courting females in front of the same backgrounds, I discovered that these spiders change how they dance in response to their surroundings! When far away, males make bigger leg movements, and when the background is more distracting, they dance from closer to the female.

Many of us might do the same things when trying to talk to a friend in a crowded party, but these spiders are doing so while simultaneously putting on a choreographed song and dance routine! And while waving to flag down someone from across the street seems simple, that behavior has never been studied in humans. We actually know more about how these spiders wave their arms for attention than for ourselves!

Undergraduate Research

When birds evolve to build together, who helps, and why?

During my undergrad, I worked as a research assistant for Dr. Gavin Leighton, who was studying how sociable weaverbirds (Philetairus socius) work together. These birds, found in southern Africa, evolved to live in large colonies and build absolutely massive straw nests that can eventually topple the Acacia trees they use for scaffolding. We learned that these nests help keep the birds warm in the desert nights, hidden details of their diet, how birds move between colonies, and that birds who are more related to their group do more building!

And an ostrich attacked us! Multiple times!