An arachnid fight club proves that tarantulas are good neighbors

Spiderday Night Writes #02

In 2005, Ariane Dor and Dr. Yann Henaut noticed something strange across villages in the southern Yucatan. Two otherwise common residents - scorpions from the genus Centruroides, and the red-rump tarantula Brachypelma vagans - seemed to be avoiding each other.

Fig 1. The tarantula Brachypelma vagans (a) and the scorpions Centruroides gracilis (b) and Centruroides ochraceus (c) live in similar types of habitats in the Yucatan peninsula, but are rarely found in the same place. Photo (a) by Carlos Valenzuela, (b, c) by Maximilian Paradiz.

It should have been easy to find both together. Dor and Henaut had plenty of experience searching for Mexican arachnids, and they knew where to look. The two scientists, both from the Mexican research institute ECOSUR (El Colegio de la Frontera Sur; “College of the Southern Frontier”), had been documenting populations of B. vagans for several years in order to conserve the species. B. vagans is legally protected in Mexico for fear of over-collection for the international pet trade. Henaut had discovered that this tarantula could be quite common in rural towns [1], and others had noted the same about Centruroides scorpions [2].

Fig 2. Brachypelma vagans has a limited home range (shown in orange). From the IUCN.

But in village after village, Dor and Henaut saw the same pattern. It didn’t matter whether they interviewed local residents, or searched themselves, night and day, week after week. If the tarantulas were living somewhere, the scorpions were scarce, and vice versa.

Dor and Henaut couldn’t help but ask why.

You might have asked the same question before. Why does this part of town have a few songbirds, but another has only pigeons? Why have do both raccoons and squirrels wander across the yard, but never at the same time of day? Why do the types of trees change as you walk throughout a forest? Nature isn’t uniform - it is diverse and constantly changing. Humans have been asking why for so long that we’ve dedicated an entire branch of science - ecology - to discovering the reasons some species live here but not there.

So what was it about these two arachnids that kept them from living in the same area? Dor and her colleagues had a few ideas. Both species could be competing for the same, crucial resource. Sometimes, two species compete for places to live, but Dor was able to rule this out. B. vagans and the two local species Centruroides scorpions (C. ochraceus and C. gracilis) prefer different types of homes. The tarantula makes its own burrows in the ground, while the scorpion hides under flat crevices. A housing shortage wasn’t the answer.

Perhaps it was food? Both arachnids hunt in a similar manner, and eat more or less the same prey: insects and other terrestrial invertebrates. If one species was a much better hunter, the other might go hungry and have trouble surviving near the superior competitor. Definitely a possibility.

However, there could be a simpler explanation. Perhaps it was food. Both arachnids are predators, after all, and their list of prey just might include each other. Most arachnids are not picky eaters; even smaller members of their own species can be fair game. To Dor and her colleagues, it seemed very likely that one of these predators was eating the other.

Who, then, was eating whom? Between the two, the tarantula was the prime suspect. Growing up to over 12cm in legspan as adults, Brachypelma vagans had weight and reach over the smaller (~2.5cm) Centruroides scorpions. But despite appearances, there was always a chance that the scorpion’s venomous stinger might be enough to make it the predator, not the prey.

There was only one way to find out for sure. To test her hypothesis, Ariane Dor had to set up an arachnid fight club.

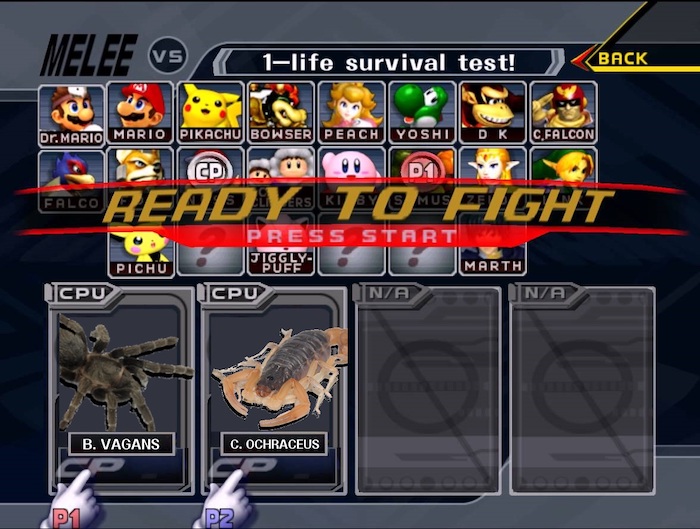

Fig 3. No items. Arachnids only. Regulation plastic box.

Like any good scientific experiment (and most good fight clubs), Dor’s fight club needed some rules. Combatants would meet in a regulation plastic box (29.5cm width x 44cm length x 23.5cm height), and would enter in a set order. First, Dor would place the tarantula in the arena, and allow it to relax for one minute. Then, Dor would introduce the tarantula’s opponent, placing it a short distance (10cm) away. For every encounter, she recorded the behavior of both combatants, as well as the final outcome.

Fig 4. Brachypelma vagans and a Centruroides scorpion square off in the arachnid fight club. Original video courtesy of Yann Henaut.

While it may seem unfair that only the tarantula was given time to get used to the arena, Henaut explains that this was to make the experiment true to life. “The natural pattern of the interaction is when tarantula is within its own territory, and attacks a a scorpion walking nearby. By their nature, these scorpions (though not all species) wander, and we see them wandering frequently, while the tarantulas hunt from their burrows.”

In total, Dor and her colleagues staged and watched 115 “fights” in their combat arena. However, only 55 of these were between B. vagans and the two local species of Centruroides scorpions. Dor also included crickets and cockroaches as opponents. She wanted to know if there was anything different between how the tarantulas handled harmless prey and a potentially harmful fellow predator.

Including the insects was a smart choice, but doing so worsened a pre-existing problem - Dor had run out of tarantulas. Ideally, there would be enough so that each individual would only have to enter the combat arena once. However, Dor and colleagues had only collected 11 tarantulas, meaning that through the 115 matches, they would have to re-use each spider 9 or 10 times. And re-using individuals in an experiment can make the data much harder to analyze.

To figure out if an experimental variable made a difference, scientists use statistical tests to compare the different things they measured. Many of these tests assume that the data is independent - that each measurement was not affected by those previously taken, and doesn’t affect future measurements. Using a tarantula more than once means that, amongst other things, that animal has a chance to learn from its previous experience and change its behavior in the future. For example, a tarantula whose first “fight” was against a cockroach might learn that being in the combat arena means it is feeding time, and behave more aggressively in future “fights” than it would have otherwise. There are statistical tests that take measuring an individual more than once into account, but these can be more challenging to both set up and interpret.

The simple solution would have been to collect more tarantulas. But, studying wildlife requires a compromise between setting up the perfect experiment, and limiting the disturbance to nature. Ultimately, Dor decided that she would re-use the tarantulas, but wait at least 14 days in between each trial, with the hope this would be long enough for the spider to forget its previous experience. Importantly, Dor and her colleagues didn’t cover anything up - they explicitly stated their choice and reasoning when publishing their work. Such compromises are a common and necessary part of science.

![A flowchart of the staged fights between Brachypelma vagans and several opponents. Most often, the tarantula was the winner, eating its opponent. Reconstructed from data presented in [3].](/img/snjc_01_fig1_x600.png)

Fig 5. A flowchart of the results Ariane Dor’s arachnid fight club. Most often, the tarantula was the winner, eating its opponent. Reconstructed from data presented in [3], and produced using Sankeymatic.com.

Luckily, Dor’s data told a clear story - the undisputed champion of the Yucatan arachnid arena was the tarantula, Brachypelma vagans. It wasn’t even close.

While the Centruroides scorpions sometimes made the first attack, they were never successful. The tarantulas claimed all victories - catching and consuming their opponent about 60% of the time, no matter who they were facing. At last, Dor and her team were able to confirm their suspicions - predation by the tarantula keeps these two arachnids apart in the wild.

Fig 6. An example of a fight between B. vagans and Centruroides gracilis. The scorpion attacks first, nipping at the tarantula’s leg, but flees after the tarantula strikes back. Original video courtesy of Yann Henaut.

In solving this ecological mystery, Dor also discovered something else - Brachypelma vagans tarantulas can be great neighbors for humans living in the Yucatan. These tarantulas have a harmless bite, stay away from human houses, and almost never attack people, preferring instead to run away. On the other hand, Centruroides scorpions wander inside buildings, and are a frequent nuisance. “Nobody likes them,” explains Dor. “I encountered them in my house: in my dishes, between pillows, etc. They hide there and stay still.” While the stings of C. gracilis and C. ochreaceus are rarely, if ever, life threatening, they can still be painful, and waking up to a scorpion in your pillow might be distressing. By eating Centruroides scorpions, B. vagans acts as a helpful town guard.

However, like in many places, people in the Yucatan have a mixed relationship with their friendly neighborhood tarantulas. “Some are very accepting of arachnids in general, [but] others reject them,” Henaut says. “Much has to do with their ethnic and social background. For example the Chol people use the tarantulas in their traditional medicine, and they care for [these spiders]. Other settlers lost this natural relationship.” [3]

Sometimes, the tarantulas face senseless violence, despite being legally protected. “In rural zones, youngsters wanted to kill them [by] flooding their burrow, [for fun],” Ariane recalls. In other cases, the spiders break their unspoken contract, albeit for a good cause. “The problem is with the males, travelling great distances in the reproductive season in order to meet his better half. They enter houses during the night and scare the city people.”

Dor and Henaut are hopeful that with time and effort, people can come to appreciate and enjoy living alongside Brachypelma vagans. “There is a always a desire to protect and conserve pretty animals, but other species are greatly important and also deserve to be protected,” says Henaut. He and other scientists at ECOSUR maintain a relationship with towns in the Yucatan, and use news articles, local TV (video in Spanish, unavailable in the USA), and outreach events (video in Spanish) to teach people about tarantulas and extol their virtues.

“A tarantula is a good caretaker of our house. She does not disturb you, as she lives quietly outside,” says Dor. Her fight club data is at the heart of her message. “She is a gluttonous predator of roaches and scorpions. Like her!”

This piece is based on the paper "Predatory interactions between Centruroides scorpions and the tarantula Brachypelma vagans," by Ariane Dor, Sophie Calme, and Yenn Henaut, and published in the Journal of Arachnology in 2011. You can access it for free via ResearchGate. This study was part of (now Dr.) Ariane Dor's PhD dissertation.

I would like to thank Ariane Dor and Yann Henaut for answering my various questions about this research, despite all the years since the study. Yann’s responses were translated from Spanish by myself.

I first posted an early version of this piece on the /r/spiders Subreddit as part of a monthly event where I share new research on arachnids.

Literature Cited:

- M'rabet, S. M., Hénaut, Y., Rojo, R., & Calmé, S. (2005). A not so natural history of the tarantula Brachypelma vagans: interaction with human activity. Journal of Natural History, 39(27), 2515-2523.

- Pinkus-Rendón, M. A., Manrique-Saide, P., & Delfín-González, H. (1999). Alacranes sinantrópicos de Mérida, Yucatán, México. Revista Biomédica, 10(3), 153-158.

- Dor, A., Calmé, S., & Hénaut, Y. (2011). Predatory interactions between Centruroides scorpions and the tarantula Brachypelma vagans. Journal of Arachnology, 39(1), 201-204.

- Machkour-M'Rabet, S., Hénaut, Y., Winterton, P., & Rojo, R. (2011). A case of zootherapy with the tarantula Brachypelma vagans Ausserer, 1875 in traditional medicine of the Chol Mayan ethnic group in Mexico. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 7(1), 12.